Kitchen’s Physics (Titanium spaghetti)

If you cook from time to time or, if you observe somebody else to cook for you at least, while the fragrance of the ingredients enhances your expectations, the experience can have two surprising results: one is that you will probably get hungry and starve perhaps if you observe for too long… The other one is that you may have a chance to understand some basics of Physics and Chemistry.

While you are boiling spaghetti, for example, as you have surely observed already, all the inside of the saucepan becomes covered by water vapour mixed, probably, with spaghetti’s particles.

After about 8 minutes (no longer if you want them cooked “al dente”), when you drain the pasta in the colander, you can notice that the internal surface of the saucepan is entirely covered by water vapour and by some spaghetti’s particles: the vapour will then become liquid and vanish quite quickly since, at the normal temperature of the kitchen, water tends the return to its liquid state.

Imagine that your hob is so powerful that you can melt in the saucepan a piece of Titanium and make it to evaporate: the Titanium’s vapour would then reach the internal surfaces of the saucepan and will stick to it as water vapour does.

The thin layer of Titanium’s vapour would become solid very quickly because of its very high melting temperature and you will never be able to clean up your saucepan anymore… This is how I understood thermal PVD coating… spaghetti is a different matter, much more complicated!

A solid titanium sputtering target by Plansee.

PVD basics (Physical Vapour Deposition)

PVD It is a process based on the strategy of to vaporize a substance (target) and to facilitate the deposition of the vapours (through a vacuum or plasma environment) onto another material (substrate). The gradual and even deposition of the vapour is to to create a solid thin film on the substrate.

It is a quite efficient method of coating which has some great advantages if compared with other more traditional systems:

Almost any inorganic material can be made to vaporize and to deposit.

There is no dispersion of gasses therefore it is more sustainable than other methods.

The coating achieved in this way is incredibly hard and durable.

There are many different types of PVD techniques but the process can always be simplified in three basic steps:

1. Vaporisation of the target (metal usually but not always),

2. Transition of the particles toward the object to be coated and

3. Deposition of the particles on the substrate to be coated.

To achieve the first step (evaporation) there is always need of some source of energy to stimulate the target strongly enough to make its particles to detach and leave.

To make the process happening in a vacuum environment allows the particles to navigate much more easily toward the substrate and to keep out all the impurities. It is possible to introduce plasma as vehicle for the transition.

There are two big families and an half of PVD process: Thermal evaporation, Sputtering and Ion Plating but many other techniques are available.

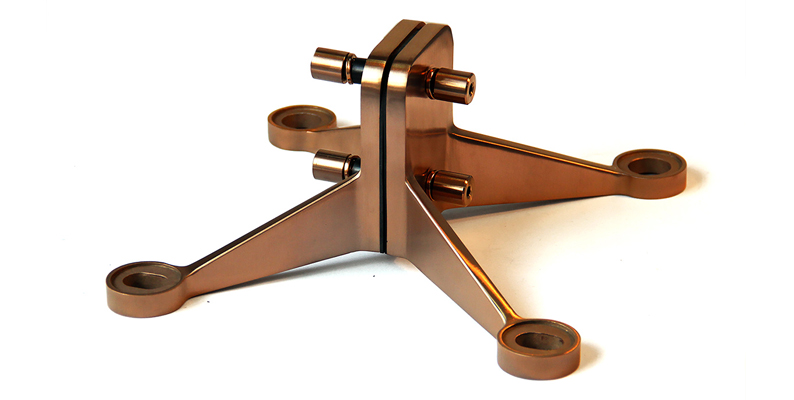

Spider bracket component for glazed roof as part of the Wandsworth footbridge construction by John Desmond Ltd, UK & Europe partner to Double Stone Steel

Thermal Evaporation

The temperature of the target has to be raised, as we said, to make it to melt and to emit vapours. This can happen for example using and electric resistance to produce heat. In the vacuum the vapours will then travel and hit easily the substrate to be coated.

This method allows keeping a very high level of “purity” and it is therefore suitable to coat high tech components: as an example the production of semi-conductor junction in micro diodes used in electronics.

There are disadvantages that can direct the choice toward other methods:

The surface to be coated needs to have a higher melting temperature than the coating metal and this limits the choice and make more complicated to mix the components.

A very high level of energy is required to eat up to the melting point the target.

The stream of the navigating particles is strictly directional and this makes it very complicated to coat evenly steps and irregularities on a non-planar object.

Spider bracket in Black is Black PVD colored stainless steel.

Stainless steel spider bracket shown in PVD coating Black is Black.

Sputtering

Well… I looked and observed carefully in the kitchen but… I couldn’t find any useful comparison for this one: please tell me if you can help! In the meanwhile I step out of the kitchen.

In this case in order to convince the particles of the target to leave its surface, the material has to be hit strongly enough by plasma’s high pressure beam (commonly argon ions).

Under the pressure of the ions stream the atoms will start to leave the surface of the target and will jump randomly in the vacuum room depositing also on the substrate.

Here a few advantages of this method if compared with thermal evaporation:

The particles jump in every direction therefore it is easier to coat evenly steps and irregularities.

The target doesn’t have to be melt therefore you don’t have to worry of not to melt the object to be coated.

The method is quite slow but can be enhanced (enhanced sputtering) with the introduction of a low voltage arc discharge at the centre of the vacuum chamber, which makes the transition of the material from the source to the substrate much quicker.

A few common objects which are often treated with sputtering: CD and DVD, scissors, cutlery, cutting tools, mirrors, glass coating.

Ordinary stainless steel spoons coated with PVD in Royal Gold and Black is Black. By Double Stone Steel.

Ion Plating

No way can I find Ion Plating near my kitchen right now but I’ll ask to my wife: she may know!

This method could be explained as a mix of the two previous ones.

The target has to be either brought to its melting temperature or hit by plasma, so that the particles start to detach from its surface and travel toward the substrate, assisted by vacuum or plasma.

The substrate has to be prepared by sputtering cleaning which means to use the process explained above but only to prepare the surface to receive the coating particles, and this can by shooting a stream of ions of the target material on the substrate.

Titanium nitride (TiN) is an extremely hard ceramic material which can typically be applied by Ion plating and it offers an incredibly good resistance on cutting tools or medical implants, and it has now a much wider field of application from jewellery to architectural finishes.

The many uses of PVD:

PVD coating enhances the durability of objects, the scratch resistance, the impact strength, the abrasion and corrosion resistance, the weather resistance, the overall durability of the object and it is used in many fields of the production.

A complete list or products would be surprisingly long but I would like to mention a few to give you a rough idea:

- Jewellery and watches.

- Machine tools (ex. drill bits and milling cutters) and common utensils (scissors, cutlery, screwdrivers).

- Medical or surgical devices (scalpels blades etc..) and prostheses.

- Bicycles and motorcycles parts (ex. Pistons or other parts which were once chrome plated).

- Microelectronics components (semiconductor devices), mobile phones, cameras.

- Aluminized PET film on snack bags.

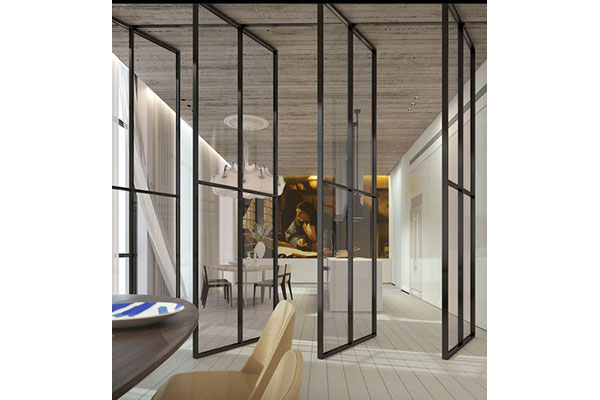

PVD is becoming more and more diffused in the fields of industrial design, furniture design and interior design: doors ironmongery, kitchen units, plumbing, taps, sheet metal finishes in general (kick plates, skirting, wall finishes).

PVD coated stainless steel can be used as cladding material on the envelope of buildings and depending on the material you decide to deposit on the substrate, you will obtain different qualities booth physical and aesthetical.

I would say, using a notorious slogan: PVD coating, from the spoon to the city!

PVD colored stainless steel in Bronze brush finish by Double Stone Steel